If you’ve heard of LNG (liquefied natural gas) projects then you know they are large scale, complex, capital-intensive, long-life infrastructure projects – ie. true mega-projects. The typical LNG project is designed to convert anywhere from 8 to 30 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of natural gas into its liquefied form so that it can be shipped around the world in LNG tankers. As with trends in the refining and petrochemicals industry, LNG projects have been getting bigger and bigger over time to improve economies of scale.

Typically, each plant will consist of one or more processing trains to turn natural gas from a gas, primarily methane, into a liquid at very low temperature. The first LNG plant was built in Algeria in 1964 had a single train processing capacity of 0.3 mtpa. Recent projects typically use train sizes of 3 to 6 mtpa, with the largest single train capacity being 7.8 mtpa in Qatar. However, the trend to larger and larger train sizes may be threatened by the challenges of building ever bigger pieces of equipment, financing mega-projects and lack of contractors willing to perform lump sum EPC projects.

Conventional LNG

The Golden Pass facility in Texas, USA being developed by Exxon Mobil and Qatar Energy is an example of the traditional mega-project approach. It was designed with 3 trains of 6 mtpa each giving total capacity of 18 mtpa with an initial cost of $10 billion USD and a five year construction time. However, construction challenges saw the EPC contractor file for bankruptcy and the project incur at least $2.4 billion USD of cost overruns and a two year delay. The project is due to start up by the end of 2025. Most other LNG projects constructed worldwide in the last decade have followed a similar approach and quite a few have experienced similar delays and cost overruns. A typical plant with two liquefaction trains is shown below.

Source: TotalEnergies

Modular LNG

However, Venture Global has pioneered a new modular design for the LNG projects together with Baker Hughes. Instead of a small number of large trains as per the traditional method, Venture Global’s projects use a large number of smaller liquefaction trains. They have two projects in operation the Calcasieu Pass and Plaquemines facilities in Louisiana, USA. In the Calcasieu Pass project, 18 trains of 0.6 mtpa are configured into nine blocks and combined to achieve 10 mtpa overall capacity. The Plaquemines project will include 36 trains across two phases for 20 mtpa of capacity.

The move away from large train capacities to smaller units, enables production to commence once some trains are installed and while construction of the remaining trains continues. The Calcasieu Pass project reached commissioning within a record 2 years and five months of the start of construction. Offsite construction of the process modules, which is nothing new by the way, enables greater cost and schedule certainty and reduced on site construction. The overall approach can bring first revenues forward, reducing financial exposure and risk. The Calcasieu Pass project is shown below - notice the nine identical liquefaction blocks in the center of the photo:

A close up rendering of the liquefaction modules is shown below:

Source: BakerHughes

Why cash flow matters most

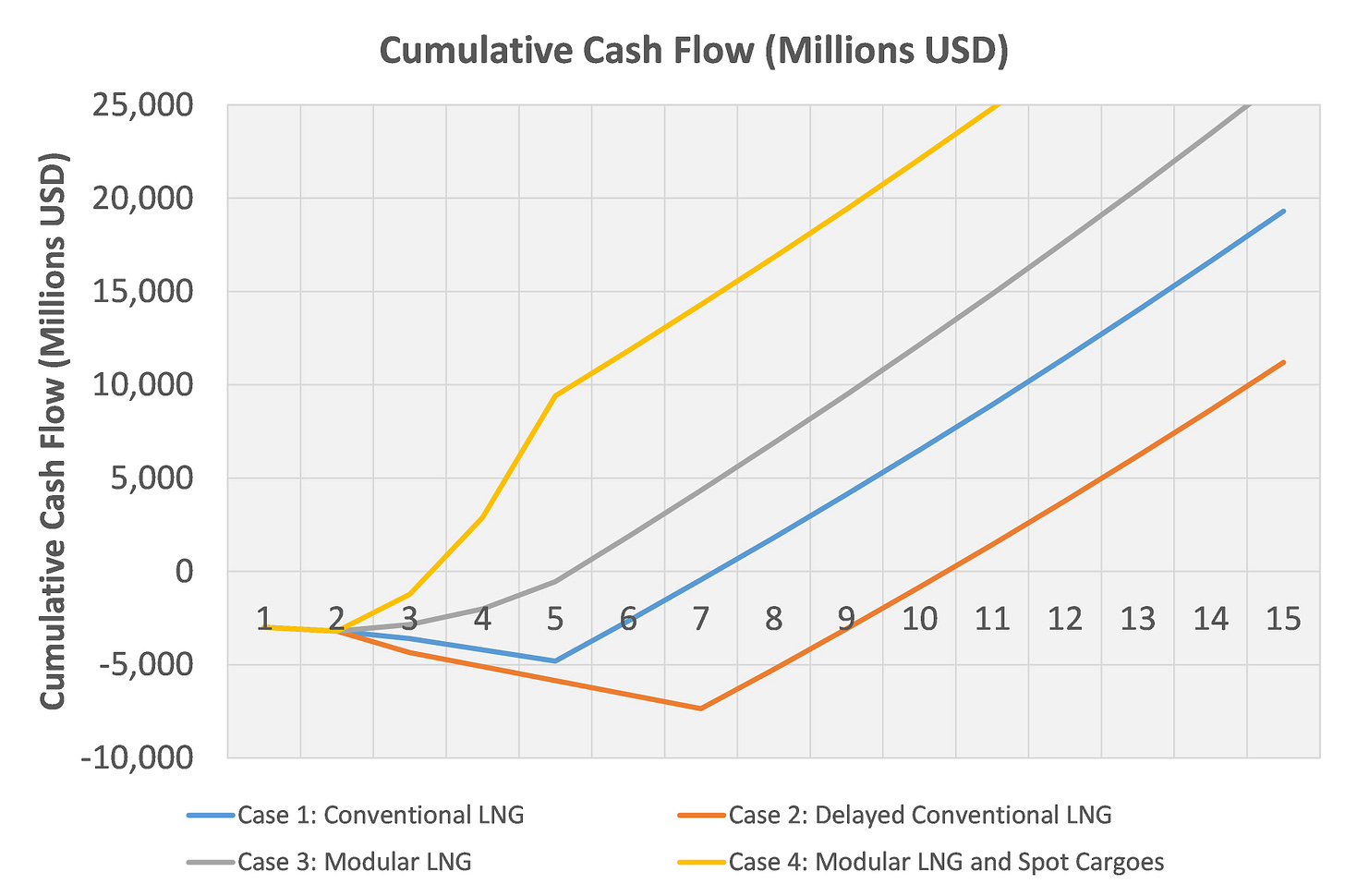

In order to illustrate the potentially profound differences in financial outcomes between the conventional and modular execution strategies, I have built a simplified discounted cash flow model for a 10 mtpa LNG project1. The conventional LNG project, like the Golden Pass facility, takes 5 years to build and commission 10 mtpa of capacity with a total installed cost of $10 billion USD, with 30% equity ($3 billion USD) and 70% debt ($7 billion USD) at 7 %/yr. Assuming natural gas is purchased at 4 $/GJ and LNG is sold at 15 $/GJ2, the project has an equity payback period of 7 – 8 years and a project IRR (real, pretax) of around 14%. The figure below shows the cumulative cash flows for this project, case 1, together with additional cases. Even though $3 billion USD of equity is needed to start, about $5 billion USD is required for working capital and to manage debt payments before commissioning. If the project is delayed by 2 years and experiences a 25% cost blowout, as the Golden Pass project has, then the equity payback period increases to 10 – 11 years as shown by case 2 in the figure and the project IRR reduces to 11%. The total equity required then balloons to over $7 billion USD.

On the other hand, the modular LNG approach, case 3, which loosely mimics the approach taken by Venture Global, enables first cash flows in year three of the five-year build and a maximum equity exposure of $3.2 billion USD. This reduces the equity payback period to 5 – 6 years and increases the project IRR to 18%. This is the approach Venture Global took with the Calcasieu Pass project. Further it seems that there were loopholes in the offtake contracts that allowed Venture Global to sell the LNG cargoes prior to completion of the full facility as spot cargoes on the international market, rather than sending them to their long term offtake customers. This loophole is being contested by the major offtakers and for certain will not be permitted in future projects. Nonetheless, Venture Global exploited this loophole and assuming a conservative estimate that these spot cargoes were sold for 35 $/GJ of LNG then we get case 4 in the figure. Remarkably, the equity payback period is just 3.3 years and the equity investment is paid back even before the facility has been fully constructed and commissioned! In this case the project IRR increases to 27%!

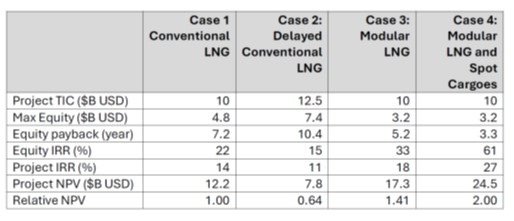

The table below provides additional economic metrics for each case I have modelled. It can be seen that the modular LNG approach reduces the maximum equity exposure and the payback period and increases the project NPV (net present value) significantly. These are big numbers – the modular LNG project has an NPV $5 billion USD higher than the conventional LNG project and $10 billion USD higher than a delayed LNG project, like the Golden Pass facility.

Typically, when modularization is discussed, the benefits are reported as being about moving construction hours from a high-cost site location to a lower cost fabrication yard, with the trade-offs being that there is invariably more steel required for a modular plant than a stick-built plant and there are higher freight costs. However, the modelling in this article shows that the key benefit of modularization is being able to bring forward cash flows, while also reducing the risk of schedule and cost blowouts. This is highlighted by the fact that in this work, the modular LNG total installed cost and build time is assumed to be the same as that as a conventional LNG plant. Of course, additional benefits could be obtained if the overall capital cost and construction time of the modular plant are reduced compared to the conventional approach as well.

Future of LNG Mega-Projects

LNG projects will remain mega-projects and economies of scale will still matter. However, modularization and bringing forward when LNG cargoes can be first delivered to customers will be key considerations for defining the design and execution of future LNG projects. Interestingly, Technip Energies has recently released their SnapLNG design, which follows this modular approach using standardized 2.5 mtpa liquefaction modules.

Based on this work, I expect that more and more LNG plants will redefine the traditional mega-project execution model and adopt a modular construction approach in future.

The simplified discounted cash flow developed for this article is not an accurate reflection of any particular project but is used to illustrate key concepts and their outcomes in a quantitative manner. Nonetheless, the results of the economic model are expected to be accurate to a first order of magnitude and reasonably represent the trends between project cases.

The 15 $/GJ sale price is assumed to be representative of the global market based on recent prices. It is noted that many LNG plants operate as tolling facilities, charging customers to liquify their natural gas at typical costs of around 2 - 4 $/GJ. This approach can limit the volatility in the spread between the purchase price of natural gas and the sale price of LNG, but also often reduces the returns.